There was once a time when memes and thiefing sugar: eroticism between women in caribbean literatureinternet-born jokes were a novelty enjoyed by relatively few people – the kind who would describe themselves as Extremely Online. Maybe you'd take pride in quoting a niche Vine that only a few select IRL friends will have seen and spent your evenings connecting with mutuals on Twitter or scrolling niche fandom accounts. Crucially, you had an understanding of internet culture that the average person probably didn't. But in 2025, it's very difficult to make that claim.

Because while internet trends and buzzwords were once an inside joke, it's now practically impossible to keep anything on social media a secret. This feels particularly pressing in the wake of BRAT summer, a concept which was cool for, approximately, five minutes and is now being referenced by Facebook mums as part of their daily vocabulary and was used in Kamala Harris' presidential campaign. Similarly, seven or eight years ago, had Jools Lebron shared her "very demure" video on Vine, rather than on TikTok last year, it might have had potential to be a private gag between you and your other very online friend, rather than the concept for at least four fashion brands' autumn campaigns. All of this to say, the idea that you can be more online than anyone else with an iPhone and an Instagram account is ostensibly extinct.

SEE ALSO: Jools Lebron, the creator of 'very demure, very mindful,' might not own its trademarkPlus, many people who once made their internet usage a personality trait called Twitter their home. But since the site has been taken over by Elon Musk and renamed to the aptly apocalyptic-sounding X, a lot of internet veterans are struggling to find a place where they can share the memes and internal monologues they once relied on the little blue bird for. Even those who migrated to TikTok are now facing the fact that the app might not exist for much longer, with the new ban in the U.S. looming on April 5 and many creators looking for alternative ways to share content online.

This doesn't mean that people aren't spending time on the internet anymore. If anything, the opposite is true, with Gen Z spending an average of 4.5 hours per day on social media, according to a report from consumer research platform GWIpublished in 2023. But finding online spaces or communities that feel specific to you or private in any sense is far more difficult than it was once. So, even if your feeds do feel individualised and personalised to you, it's hard not to feel that, in one way or another, you're consuming more or less exactly the same content as anyone else.

The main reason for this is, simply put, algorithms. You've probably noticed that the way you're served content on almost every social media app — be it TikTok, Instagram or X — nowadays has changed. Where once you'd see posts created by people you chose to follow, now apps mainly serve up recommended content based on people and things it thinks you might be interested in. "The platform’s algorithms base their recommendations on content you have liked and engaged with," explains Dr. Carolina Are, social media researcher at Northumbria University’s Centre for Digital Citizens.

There are benefits to this, of course, in that it might help you come across content that you really enjoy and wouldn't have discovered otherwise. This also explains why meme culture has become so widespread, as if a fairly small group of people are enjoying a particularly funny meme, the algorithm will push this out to a much wider number of people very quickly. "This has become a faster, more efficient and more economic, if not always accurate, way of governing swathes of content worldwide," Are says.

But it also means it's very hard to form and maintain small communities based on common interests or experiences online nowadays, as they're often catapulted to far more people than intended, whether they're the correct audience or not. Plus, remaining part of a digital community can be difficult when you're being served so much new content rather than the posts created by accounts you follow.

"It feels like the algorithm wants you to see stuff you don't like."

Izzy, who is 27 and lives in London, has been using social media since 2009 and spent most of the 2010s very engaged with what was then Twitter. "I used to tweet hundreds of times a day," she says, adding: "I've definitely always considered myself to be very online. I do enjoy being that person that knows every internet reference and meme." However, Izzy recently decided to stop using X and her decision was based on the app's algorithm: "It feels like the algorithm wants you to see stuff you don't like so that you engage with it and it also shows your stuff to people who won't like it," she says, explaining that this was making her experience of using social media almost entirely negative.

This is in stark comparison to the way Izzy and many other very online people would use apps like Twitter in the early to mid 2010s, connecting with mutual followers you probably considered genuine friends and finding a safe space of sorts on the internet. Often when you're scrolling now, it probably feels less like you're engaging with real people or friends, given that so many brands have such an active presence on social media nowadays. And not to mention influencers who, although are undoubtedly real-life people (unless you count the AI influencers), don't always necessarily feel like it when you consume their content through your screen.

"Algorithms like TikTok's For You Page push popularity and not network building, encouraging users to engage as ‘the public’ rather than someone to have a meaningful interaction with," Are says. "The follower is no longer a peer, they’re the audience, while the creator is more similar to a conventional, mainstream media broadcaster than to an independent creator."

"My social feeds are dominated by influencers and personalities."

"My social feeds are dominated by influencers and personalities," says 27-year-old Charlotte, who now works on social media but, like Izzy, was very online throughout her teenage years. "You do create this parasocial relationship where you feel like you know them," she adds. Izzy agrees that this has been one of the biggest changes in her experience of using social media during the past decade: "I do think brands and influencers dominate my social media a lot more - it's constantly ads on my feed. I choose to follow my friends and often I don't see their stuff," she says.

SEE ALSO: What are parasocial relationships?This is one of the main shifts we've seen in the content that's posted and consumed on social media now and one of the reasons why those very online communities have disintegrated over the years. "The sense of community can be lost while celebrity is gained and content becomes about selling instead of connecting," Are says

"Ten years ago, I made friends through twitter and even though there were some people who would feel unattainable in a way, it was nothing like it is now," Charlotte says. In this way, the death of being very online goes a lot further than just the dissemination of meme culture and the lack of inside internet jokes. It reflects the lack of space for genuine interaction and meaningful communities online right now, something that was once considered to be one of the main plus sides of social media.

"There aren't really niche internet jokes anymore..."

And given that social media is so heavily commercialised nowadays, with ads taking up every other post on apps like Instagram and X, and influencers, even smaller creators, actively trying to monetize their content, it feels as though it's lost any sense of playfulness and fun. "There aren't really niche internet jokes anymore because you have trend forecasters and people whose jobs it is to hop on these trends and make it about a brand," Izzy says adding: "The memes aren't as funny when you know they're going to be co-opted."

No one scrolling through Tumblr in 2014 or tweeting about One Direction in their teenage bedroom would have predicted that they were living through the golden age of social media, but that might just be the case. It's certainly safe to say that millennials who once considered themselves very online were certainly having more fun on social media than young people probably are now, with 30 percent of young people aspiring towards a career as an influencer, undoubtedly spending their time scrolling thinking about how they can monetise their favourite meme and figuring out how to hack the algorithm to promote their content.

So, even though you might lament the fact that you don't have a hold over internet culture anymore and that even trying to do so can be depressing, be thankful that now is probably the best time to become very, very offline.

Previous:The Best Skyrim Mods

Best Ninja deal: Save $50 on the FrostVault 45QT cooler

Best Ninja deal: Save $50 on the FrostVault 45QT cooler

We Are Made of Memories: A Conversation with Mia Couto by Scott Esposito

We Are Made of Memories: A Conversation with Mia Couto by Scott Esposito

Outside the Paris Pavilion by Sadie Stein

Outside the Paris Pavilion by Sadie Stein

A Bigger, Brighter Screen by Lorin Stein

A Bigger, Brighter Screen by Lorin Stein

Apple MacBook Air deal: $899 at Best Buy

Apple MacBook Air deal: $899 at Best Buy

Laughing in the Face of Death: A Kurt Vonnegut Roundtable

Laughing in the Face of Death: A Kurt Vonnegut Roundtable

Rumors of the Death of the Book Greatly Exaggerated, and Other News by Sadie Stein

Rumors of the Death of the Book Greatly Exaggerated, and Other News by Sadie Stein

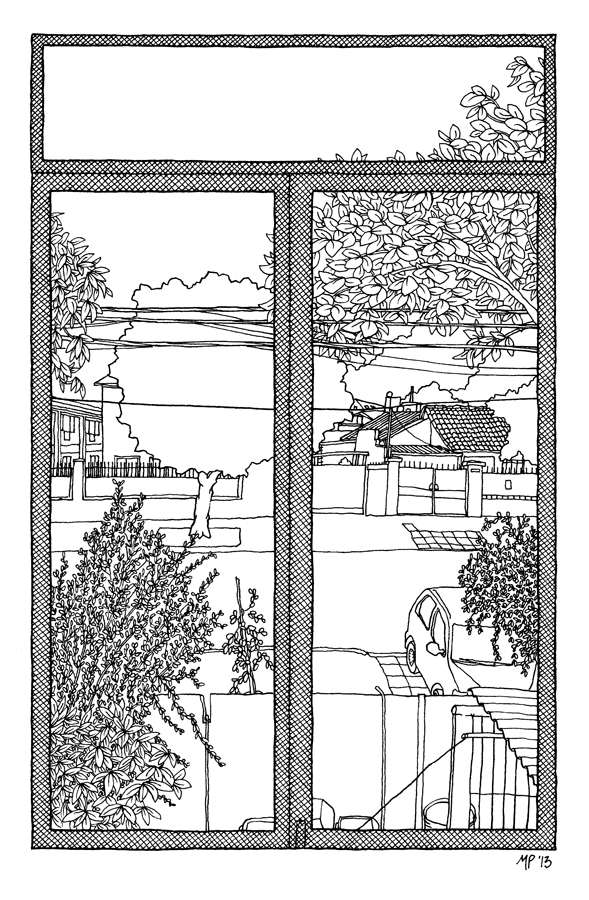

Alejandro Zambra, Santiago, Chile by Matteo Pericoli

Alejandro Zambra, Santiago, Chile by Matteo Pericoli

Fritz vs. Monfils 2025 livestream: Watch Australian Open for free

Fritz vs. Monfils 2025 livestream: Watch Australian Open for free

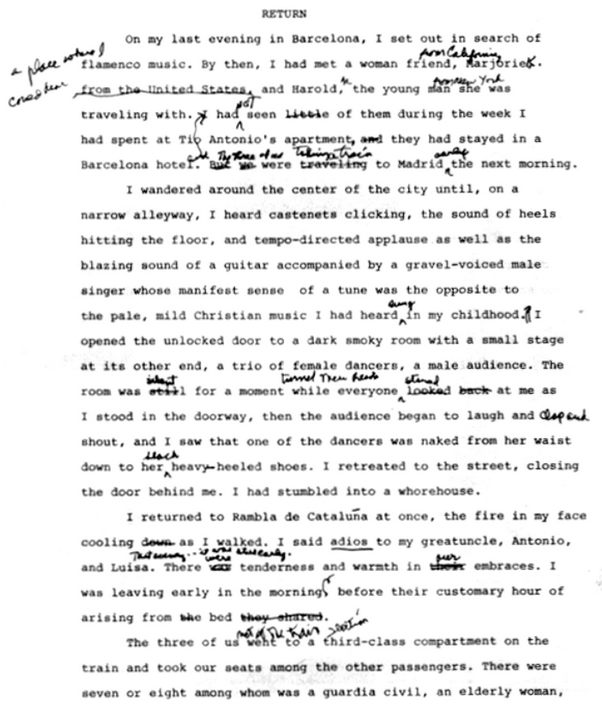

Paula Fox, Work in Progress by The Paris Review

Paula Fox, Work in Progress by The Paris Review

Creators talk accessibility and building inclusive spaces at VidCon 2025

Creators talk accessibility and building inclusive spaces at VidCon 2025

No Amusement May Be Made by Evan James

No Amusement May Be Made by Evan James

Rumors of the Death of the Book Greatly Exaggerated, and Other News by Sadie Stein

Rumors of the Death of the Book Greatly Exaggerated, and Other News by Sadie Stein

A Bigger, Brighter Screen by Lorin Stein

A Bigger, Brighter Screen by Lorin Stein

Best cooler deal: Save $50 on the Ninja FrostVault at Amazon

Best cooler deal: Save $50 on the Ninja FrostVault at Amazon

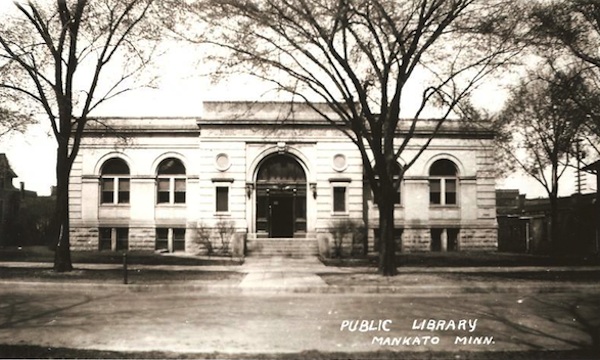

Happy Birthday, Maud Hart Lovelace by Sadie Stein

Happy Birthday, Maud Hart Lovelace by Sadie Stein

Finding Marie Chaix by Harry Mathews

Finding Marie Chaix by Harry Mathews

Adieu White Street, Bonjour High Line by Lorin Stein

Adieu White Street, Bonjour High Line by Lorin Stein

Sam's Club membership discount

Sam's Club membership discount

Hell Is Other Cats by Sadie Stein

Hell Is Other Cats by Sadie Stein

How livestreaming dominated 2016Trump says Happy New Year in the most Trump wayRyan Gosling to play Neil Armstrong in 'La La Land' director's moon landing biopicCarrie Fisher and Debbie Reynolds to be buried togetherCollege memories flood Twitter after red Solo cup inventor diesThese are the top 16 movies of 2016Snapchat's 10 most popular lenses of 2016President Obama sanctions Russia for hackingHow to never touch anyone ever againThe surprising 'Home Alone' and 'Friends' connection you never noticedFacebook Live wants users at any cost—even porn, piracy, and polling5 VR safety tips to stop you from destroying your homeCongratulations, internet: The Mannequin Challenge finally made it to spaceWhat we do and don't know about Russia's interference in the presidential election16 incredible quotes from 16 incredible books that got us through 2016Carrie Fisher and Debbie Reynolds documentary to premiere on HBOEmma Watson singing in 'Beauty and the Beast' leaked by Belle dollTrump sings about his presidency in the ultimate parody remixTech for New Year's resolutions to stay fit and healthyThis app wants to help you invest in companies that align with your morals 200+ of the best Walmart Cyber Monday deals (live now) Online misinformation runs rampant during coup attempt in Russia Cooking with Bohumil Hrabal by Valerie Stivers One Missing Piece by Jill Talbot Amazon Cyber Monday TV deals 2023: Fire TVs, cheap QLED TVs, and more Coveting Cartier Necklaces and Celtic Torques at the Met by Julia Berick Popular subreddits end their Reddit protest with *only* pictures of John Oliver In Defense of Puns by James Geary The Shocking, Subversive Endings of Taeko Kōno’s Stories by Gabe Habash The Touch of Dawn by Nina MacLaughlin Staff Picks: Whisky Priests, World’s End, and Brilliant Friends by The Paris Review 'The Idol': How to use ice cubes during sex Ludmilla Petrushevskaya, Fabulist and Fabulous Singer by The Paris Review Cyber Week unlocked phone deals: Apple, Google, Samsung, more Best Cyber Monday Roomba deals at Amazon 2023 Cyber Monday headphone deals still live: Bose, Apple, Sony, and more Apple shares most popular podcasts and books of 2023 In Bed: The Mattress as Art by Larissa Pham Apple Card ends partnership with Goldman Sachs: 3 reasons we saw it comin' Cyber Monday 2023: Everything you need to know

3.6448s , 10221.0390625 kb

Copyright © 2025 Powered by 【thiefing sugar: eroticism between women in caribbean literature】,Miracle Information Network